Overview

As noted in our charter, the purpose of the Federated Identity Community Group is to provide a forum focused on incubating web features that will both support federated identity and prevent opaque, uncontrollable tracking of users across the web. The community group recognizes the need to balance privacy concerns against the need to explore innovative ideas around federated authentication on the web. The initial work of the group focuses on the short-term goals as prioritized by the urgency of changes already underway, such as the phasing out of third-party cookies.

At the time of this report, the community group has several outputs, including a detailed list of federated authentication protocol elements and how they will be impacted by changes in third-party cookies, link decoration, and bounce tracking. The community group has also begun to document how different proposals and protocol elements might be used to mitigate the changes being introduced as browsers add mechanisms to prevent tracking. The group has one formal work item, the Federated Credential Management API, that explores one potential path for some services to follow as third-party cookies are deprecated.

Given the complexity of the use cases surrounding federated authentication workflows, it is unlikely that any one proposal or work item in any standards organization will resolve all the issues that will arise as the low-level primitives on the web change or are removed. Part of the work of the community group is to gather sufficient information that developers will be able to determine what mix of protocol elements, browser APIs, and other tools will meet their needs in continuing to use federated identity on the web.

Terminology

a glossary of terms that have specific domain definitions and clarify possible collisions as they relate to this context.

Credentials - When browser vendors refer to credentials, they typically mean an object which allows a developer to make an authentication decision for a particular action. (See also https://www.w3.org/TR/credential-management-1/#core)

Sign-in - the act of authenticating into an existing account. While the user may experience this as part of the overall UX for a registration process, it is a logically distinct activity from Sign-up.

Sign-out - the act of ending one or more sessions.

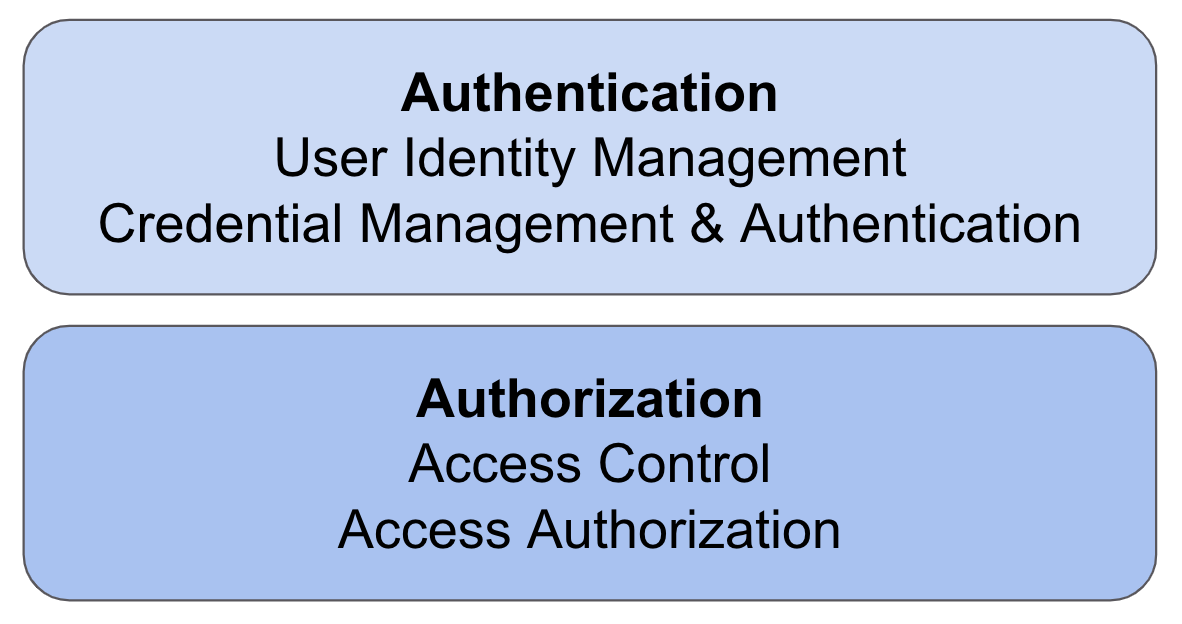

Sign-up - the act of establishing or registering an account with a service. While an end-user can sign-up and sign-in simultaneously, logically they are two separate actions. (Similar to how some sites make the choice of “if you can authenticate, you are authorized to use/access the service” despite authentication and authorization being two logically distinct actions.)

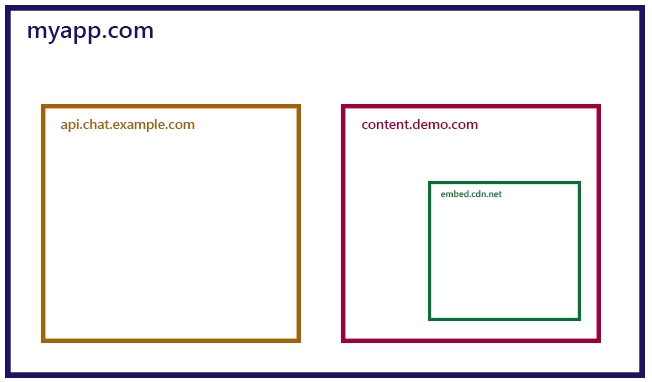

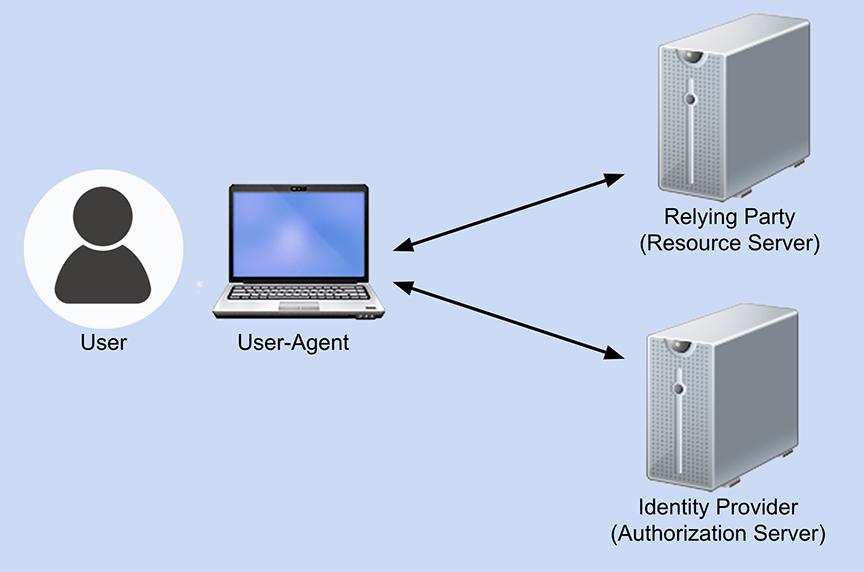

Understanding Basic Federated Identity Flows

In any federated identity flow, there are effectively four parties involved: the user, the user-agent (the browser or app) the user is employing, the Relying Party that manages the resource the user is trying to access, and the Identity Provider that is validating the user’s access.

Generally speaking, the frameworks and protocols involved in identity federation most often are OAuth 2.0, OpenID Connect (OIDC), and SAML 2.0. OAuth is a framework for providing authorization to protected resources. OpenID Connect is an identity layer that works on top of OAuth and handles the authentication of the user. Authorization indicates that the user should have access to a resource, but it does not serve to connect the user to an existing account. Authentication, on the other hand, is the process of establishing that the entity requesting access can be connected with an existing account; it does not indicate whether the user should have access to anything.

SAML is similar to OpenID Connect in that it also handles the authentication of the user. SAML, however, is an XML-based framework and uses XML in its communications.

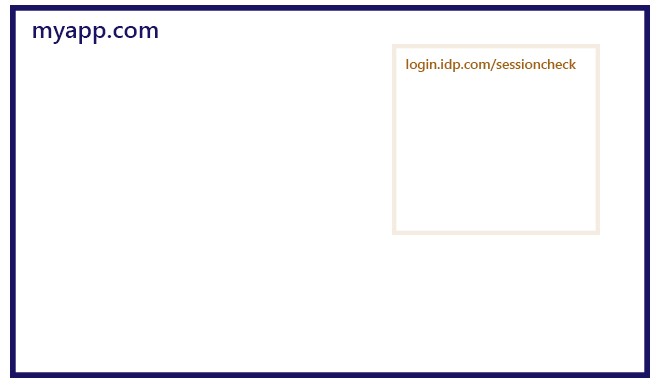

Currently, it’s possible for the Relying Party and Identity Provider to collect information about the user that the user might not be aware of. It’s also possible for different organizations to collude with one another to join the data they’ve collected about a user (especially when the credentials used include a global identifier such as a user’s email address). As a result, user-agents are trying to take a more active role in assuring their users’ privacy online, but there are still questions as to what role a user-agent should play in federated identity flows.

There are four possible scenarios for the user-agent’s role:

- The status quo is kept, and the user-agent facilitates but doesn’t take an active role.

- The user-agent does its best to highlight any potential privacy risks for a user but doesn’t try to mitigate the risks directly. Instead, the user-agent would ask the user to grant their permission to continue. This is referred to as the permission-oriented approach.

- The user-agent takes a more active role by taking on some of the current Identity Provider responsibilities. In this case, the user-agent manages the user interface and account options shown to the user. This is called the mediation-oriented approach.

- The final scenario is one where the user-agent takes on the most active role. In it, the user-agent would not only manage the user interface presented to a user but would also manage the presentation of the required tokens to the Relying Parties. The Identity Providers would still be responsible for issuing tokens but would be delegating the submission of them to the user-agents. This is why it’s referred to as the delegation-oriented approach.

Each option has compelling pros and cons that trigger debate. With the first option, if the user-agents don’t limit how third-party cookies can be used, they will be accountable for the resulting privacy issues and concerns - making this an unlikely course of action. If the user-agents continue with the planned privacy changes for third-party cookies, but do nothing else, then the areas of identity federation that rely on third-party cookies currently will stop working. This is also untenable, so the first option seems unlikely.

With the second option of the user-agents highlighting the privacy risks for their users, it does give users control over their privacy choices. However, historically privacy prompts like this have proven to be ineffective at best and a negative user experience at worst. It places all of the responsibility with the users to understand the consequences of their choices. Some users might welcome that, but others certainly wouldn’t.

The third mediation option removes some of this burden from users, but in turn it also complicates how the protocols would actually need to work. It requires a significant amount of work on the standards that define identity federation, and in turn, it will require a yet-to-be-determined level of implementation work. It’s not a trivial change.

Finally, the fourth option, with the user-agent taking the most active role, does protect users from having either the Relying Parties or Identity Providers tracking them. However, it would also be the most complicated change and would take the greatest amount of work from not only the user-agents, but also the Relying Parties and Identity Providers themselves. Specifically, the delegation-oriented model is not likely to be backwards compatible with the current deployment, so it’s not a good option as a preliminary solution (at least, as a mutually exclusive option). The greater the amount of work involved, the longer it typically takes to execute a change - and the deprecation of third-party cookies is a deadline for this since third-party cookies are often currently needed.

The other concern with the fourth option is that, while the tracking risk from Relying Parties or Identity Providers is decreased, it doesn’t stop the user-agent itself from engaging in user tracking (although trying to restrict this would be something of an unrealistic requirement). However, it does limit the number of potential bad actors, but it doesn’t necessarily eradicate the tracking risk altogether because if the user-agent itself is a bad actor, the user’s privacy would still be at risk.